The Sullivan Review of data, statistics and research on sex and gender

The conflict between reality-based norms and gender identity theory in the United Kingdom.

The Review of data, statistics and research on sex and gender in the United Kingdom, led by Professor Alice Sullivan of University College London, has the potential to do even more than the Cass Review to loosen the grip of gender ideology on public institutions. The Review has issued two reports. Report 1, published in March 2025, reviews data collection practices in everything from health care to transportation and finds that changes over the last ten years have led to confusion between sex and gender identity in administrative and survey data.

The basic recommendation of Report 1, that data on sex and gender identity should be clearly separated, should be uncontroversial, but has met with widespread resistance. Report 2, published in July 2025, explains why. The growth of bureaucracy, erosion of academic autonomy and the introduction of Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) programs have “provided levers for activists pursuing agendas which are not compatible with the truth-seeking mission of universities.” This has created significant barriers to any research which seeks to treat sex as real and important.

The Review was commissioned in February 2024 by the former Conservative government. Unlike Hilary Cass, who was selected for her perceived neutrality, Sullivan is known for her gender critical views both in her academic work and as an advisor to the advocacy group Sex Matters.

Report 1 was largely technical. It was met with the expected condemnation from trans-activist groups but the Health Secretary has confirmed that the government will implement its key recommendations. The Review received further support from the decision of the UK Supreme Court in the For Women case, where it was held that the terms man and woman, in the Equality Act 2010 refer to biological sex.

Report 2 is more controversial. It is a strongly worded indictment of academics who have abandonned truth-seeking for politcal activism and the university bureaucracies that have enabled them.

Loss of Data on Sex

The basic premise of Report 1 of the Review is summarized as follows:

Sex is a key demographic variable and collecting high quality, robust data on sex is critical to effective policy making across a wide range of fields, from health and justice to education and the economy.

By sex, the Review means biological sex or sex at birth. This is distinguished from “legal sex” which, in the United Kingdom, means sex designated in a Gender Recognition Certificate.

However, the Review found that, in the United Kingdom, public bodies, private charities and major public opinion researchers can no longer be counted on to provide accurate data on sex. It concludes that “the meaning of sex is no longer stable in administrative or major survey data.” The term sex may refer to sex at birth, legal sex or an inner sense of self. Published data often fail to make it clear how sex has been defined.

Prior to 1990, surveys asked about sex with male and female being the only options. Between 1990 and 2014, the term gender began to be used as a synonym for sex, but the answers were still only male or female. After 2015, gender began to be used as a synonym for gender identity and non-binary options or “prefer not to say” began to appear.

The basic recommendation of Report 1 is that sex and gender identity are distinct characteristics and that it is necessary to collect data on both. It discusses the scientific, legal and political case for separating sex and gender identity.

The Review acknowledges that some trans, non-binary or gender diverse people will be uncomfortable with disclosing their sex. It notes that discomfort with disclosing particular information is common and varies widely between individuals. However, the fact that a small number of individuals find a question sensitive is not justification for not asking the question. Sex is extremely important information and the public benefit of collecting information on sex far outweighs the discomfort of a small portion of the population.

Furthermore, the Review rejects the idea that sex and gender identity are in competition and that it is not possible to be respectful of gender identity without erasing sex.

The Review noted that disinformation about people with Differences of Sexual Development (DSD) conditions, sometimes known as “intersex” conditions, is often misused to support the argument that sex is not binary. People with a DSD condition are either male or female. They tend to think in terms of their particular medical condition rather than identifying with the umbrella term intersex. The Review recommended against including the term “intersex” in routine data collection. There is no agreement on which DSD conditions qualify as “intersex” and the prevalence of these conditions is too small to be useful for analytical purposes.

Shortly after Report 1 was published the UK Supreme Court delivered a judgment in For Women Scotland Ltd. v The Scottish Ministers which held that the terms “man” and “woman” in the Equality Act (2010) referred to biological sex. An addendum to Report 1 notes that the judgment is consistent with the Review’s recommendation that sex and gender identity should be treated as distinct characteristics.

The Need for Clarity

Attempts to collect data on both sex and gender identity have encountered problems. The 2021 England and Wales Census included a question on gender identity, but it was not always understood, particularly by respondents with limited knowledge of English. The number of Muslims who were recorded as identifying as transgender (1.5%) was three times higher than the level in the general population (0.5%) and 2.2% of respondents who did not speak English well were recorded as transgender compared to 0.4% of those who did speak English well.

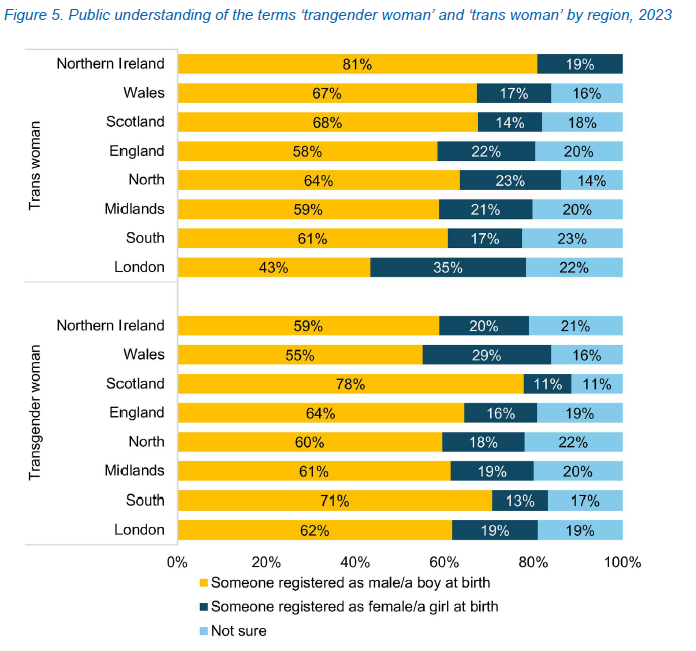

Some of the basic terminology used to collect data on gender identity is not well understood by the general public. For example, a survey conducted in 2023 found that in London, 43% of respondents thought that “trans woman” referred to someone registered as male at birth, 35% thought it referred to someone registered as female at birth and 22% were not sure. The Review concluded that further research was needed to assess public understanding of terminology and to develop appropriate questions.

Health Care

Knowing a patient’s sex is crucial for both the provision of health care and for research, but the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK does not record this information in a consistent way. England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland all have different record-keeping systems but they all record self-described gender and allow patients to change their gender marker on request. Specialized services and clinics may keep their own records of sex, gender or gender identity, but there is no consistency in what they record.

The lack of reliable information on patient sex has compromised patient safety. Many cancer screening tests are sex-specific and patients with changed gender markers may be called for unnecessary screening tests or miss out on tests they require. There is also a risk that laboratory tests will not be correctly assessed if the patient’s sex is not correctly recorded. There is no minimum age for changing a gender marker and parents may request a change of gender for their children. Shortly after Report 1 was issued, the health secretary ordered the NHS to stop changing gender markers on children’s medical records.

Inconsistent policies on data on sex also affect health research. The Medical Research Council requires researchers to use both sexes as a default in experimental design unless there is strong justification for a single-sex study. However, it does not provide guidance on data collection.

The European Association of Science Editors has created the Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) Guidelines, which have been endorsed by major academic journals. The Guidelines and their supporting materials say that sex, gender and gender identity should be separated but they are often ambiguous. The definition of sex refers to it as a “set of biological attributes” which are “usually categorized” as male and female. There is no guidance on how data on sex should be collected.

Policies at individual journals vary. The British Medical Journal does not have explicit guidelines for reporting sex and gender, but contributors are encouraged to use the SAGER Guidelines. The Lancet has its own policy which states that sex has multiple definitions and that sex and gender exist on a spectrum. It advises that data collection on gender identity should be prioritised, with a secondary question on sex. Nature / Springer follows the SAGER Guidelines and includes a definition from the American National Institutes of Health which states that sex is biological and gender is socially constructed.

Barriers to Research

Report 2 of the Review expands on the difficulties of conducting research on sex and gender. The Review finds that academics and researchers who hold the “gender critical” position, which it defines as the belief “that biological sex is real, important, immutable and not to be conflated with gender identity,” face relentless opposition in UK universities.

The Review acknowledges that the term gender-critical is not universally accepted and that it does not describe a single position or consistent set of beliefs. The term is used to describe a range of activities including scientific research on sexual differences, objections to gender self-identification policies, questioning the affirming model of gender medicine and arguing for spaces and sports for women and girls based on sex.

Gender-critical academics of all types are under constant pressure to self-censor. Those who do not face harassment, denial of research funding, cancellation of events, and even loss of jobs. The Review does not hesitate to identify the problems and assign blame:

The evidence we have reviewed does not support a narrative of a ‘polarised’ ‘toxic debate’ where ‘both sides’ have behaved badly. Rather, there is evidence of some university staff who disagree with gender-critical views behaving in ways that are outside the norms of the scientific and scholarly community, and which challenge these norms. The toxicity is generated by behaviours rather than by conflicting viewpoints as such. The staff involved in such behaviours constitute a small minority of university staff, yet the effects of tolerating and encouraging these behaviours are serious.

Gender Identity Theory vs. Reality

The problems the Review identifies are inherent in the nature of “gender identity theory,” which is defined as the “negation of at least one of the four aspects of gender-critical belief: in other words, the assertion that biological sex is not real and/or not important and/or not immutable and/or that gender identity and sex cannot be clearly distinguished.”

The Review starts from the premise that the university should be a “reality-based community as described by Jonathan Rauch in “The Constitution of Knowledge.” The norms of a reality-based community require that truth claims must stand up to checking against evidence and not depend on the identity of those making the claim. This is the basis of the scientific method. Gender identity theory is rooted in postmodernist theory which sees knowledge as socially constructed and truth seeking through dialogue and testing of evidence as a simple exercise and power. These ideas have affected both students and faculty. The Review notes that:

For some academics, the line between activism and research has been completely blurred, so that ‘research’ ceases to be a truth-seeking activity. As we will discuss below, some adherents of gender-identity theory also believe that disagreement can constitute violence towards people they see as having marginalised identities.

The result has been a breakdown of academic norms in the field of gender studies. Ad hominem attacks on gender critical feminists are an accepted part of academic writing. A paper presented by a graduate student at a conference at the London School of Economics described a fantasy of holding a knife to the throat of so-called Trans-exclusionary Radical Feminists (TERFs).

The same attitudes have spread through the student population. The Review reports that:

Polling of undergraduates has shown that the proportion of students with illiberal views regarding free speech increased between 2016 and 2022. When asked what rights students and staff should have to respond to an event they dislike, in 2022, 20% said they should be able to ‘stop the event from happening’ (up from 8% in 2016) and 12% said they should be able to ‘disrupt the event’ (up from 5% in 2016). Thirty-six percent of students agreed that academics should be fired if they ‘teach material that heavily offends some students’ (over double the 15% of students saying this in 2016).

Bureaucracy in Education

The erosion of commitment to freedom of expression in the university community has coincided with a growth in bureaucracy. The Review finds that, over the last decade, universities have experienced an increase in the proportion of staff in administrative and management roles relative to teaching and research staff. At the same time, there has been a decline in the number of traditional permanent contracts and an increase in the proportion of teaching and research staff on insecure contracts. The result has been a decline in academic autonomy and democratic governance. The Review finds that “the majority of academics engaged in teaching and research have little say or voice in how their universities are run.”

Equality, Diversity and Inclusion

University bureaucracies have introduced so-called “Equality, Diversity and Inclusion” (EDI) programs into the United Kingdom. These programs were imported from the United States where EDI is known as Diversity, Equity and Inclusion or DEI.

The problem with EDI/DEI programs is that diversity does not include diversity of belief. The Equality Act 2010 in the United Kingdom prohibits discrimination on the grounds of belief and, in the case of Forstater v. CGD Europe, an employment tribunal found that gender critical beliefs are protected beliefs. However, university EDI bureaucrats have ignored this decision and instead formed partnerships with Stonewall and other transgender activist groups to impose gender identity theory on the entire university. EDI is also not genuinely inclusive. Gender-critical lesbians and gays have found that they are not welcome in campus groups that purport to speak for the LGBTQ+ community. EDI bureaucracies sometimes play an active role in suppressing gender critical beliefs.

Compiling the Evidence

Report 2 provides extensive documentation of the tactics used by transgender activists. Appendix 1 provides 50 examples of open letters, circulars and statements denouncing gender-critical individuals and views, dating back to 2015. The language in these documents is usually hyperbolic and sometimes abusive and defamatory. Many of the signatories to multi-signature letters appear to have no connection to the United Kingdom University System.

There is a detailed discussion of the campaign against Kathleen Stock at the University of Sussex and Appendix 3 reproduces materials from the “Stock Out” campaign. The Report also reproduces speaker notes for a talk Michelle Moore gave to the Free Speech Union in July, 2024 which describe the harassment she suffered for raising concerns about medical transition of children.

A section on legal cases discusses the case of Phoenix v The Open University in which an Employment Tribunal found that the Open University harassed, victimised and wrongfully dismissed Professor Jo Phoenix for her gender critical views. The Report reviews 13 other cases of instructors or students who have been attacked for gender-critical views that have been reported in the media or by social media. It notes that that there are similar cases which have been settled in private. The Free Speech Union (FSU) has 2,416 closed cases since the began in February 2020. Fifteen percent of these cases (355) were related to higher education and 102 were related to gender identity issues. The FSU was unable to identify any complaints brought by opponents of gender critical views.

The Review conducted a survey of academics asking for accounts of barriers to research under the following subject headings:

1. Research ethics processes;

2. Barriers to research funding;

3. Barriers to data collection;

4. Barriers to publication;

5. Self- censorship and chilling effects;

6. No-platforming;

7. Barriers to holding events;

8. Disinvitations from projects or collaborations;

9. Discrimination by university administrators or services;

10. Bullying, harassment and ostracism;

11. Complaints, including coordinated complaints;

12. Management behaviour;

13. Compelled speech;

14. Barriers to career progression;

15. Institutional policies and training;

16. Barriers affecting students;

17. Other.

There were 130 valid responses. Fifty-seven percent of respondents agreed with gender critical beliefs and 39 percent disagreed. Sixty percent of respondents described their views as left-wing or fairly left-wing. Sixty-six percent of respondents were female.

A group called the Feminist Gender Equality Network published a call for submissions and a template which contained recommended responses to each question. These template responses were easy to spot and the Report shows the results with the template-based responses excluded. The Report reproduces the entire template in Appendix 2.

The Report noted a marked difference between the gender-critical and anti-gender-critical responses. The gender-critical responses included extensive details and could often be confirmed from information in the public domain. The anti-gender critical responses tended to be vague and difficult to verify.

The largest number of responses concerned self-censorship and chilling effects. Responses from the gender-critical position identified the behaviour of colleagues or supervisors as the main source of pressure to self-censor. Responses opposed to the gender-critical position were more likely to refer to external pressures from the media or social media.

The second largest group of responses concerned bullying, harassment and ostracism. The Review noted that when evaluating these responses it was important to distinguish between “pointed and even harsh critiques of ideas, which are perfectly legitimate and indeed form part of the university's raison d'être, and ad hominem attacks on individuals, which are unscholarly and can even constitute, in some instances, unlawful harassment.” There were responses on both sides of the issue but the responses on the gender-critical side were more extensive and detailed than those on the opposite side.

Barriers to publication were the third major response area. Some journals engage in policing of language and concepts which disallows any clear reference to biological sex. Editorial decisions appeared to be “influenced by factors unrelated to academic rigour.” For example, one high-journal had a policy of not publishing articles on trans healthcare unless they were reviewed by a transgender layperson or an advocacy group which supported gender-affirming approaches to healthcare. Responses from those opposed to the gender-critical position emphasized hostile media reaction rather than barriers to actual publication.

Gender-critical respondents reported significant barriers to holding events. These included co-ordinated campaigns to demand cancellation of events and intimidation at the actual events. Management provided little support or made unreasonable demands for security at the events. Opponents of the gender-critical position would insist that an event provide “balance” and then force cancellation of the event by refusing to attend. The responses from opponents of the gender-critical position did not provide any instances of actual cancellation of events but mentioned concerns about “dangerous” attendees, which appeared to mean people who might ask critical questions.

The Report concludes that there has been an activist campaign ”aimed at closing down research and enquiry that starts simply from the unexceptional position that sex is immutable, binary and salient in particular contexts, and has not only been tolerated but conceded to, even placated, at the highest level in institutions.”

Research Ethics

The introduction of EDI has been accompanied by changes to the Research Excellence Framework (REF), which is the mechanism for allocating government funding for research in the UK. The REF has increased the administrative work required by researchers and is being used to impose an EDI agenda on research.

The Review notes that research ethics committees have abused their powers to impose gender identity theory and other aspects of the EDI agenda on researchers and recommends measures to end the politicization of the ethics review process. The scope of ethics review should be limited so it is not required for secondary data analysis, undergraduate research, and low risk research that does not involve actual medical treatment or work with vulnerable populations.

Recommendations

The key finding in Report 2 is unequivocal:

Academics and others who have questioned gender-identity theory have faced freedom-restricting harassment (Khan 2024), with severe personal and professional consequences. This is not a question of ‘both sides’ behaving badly in a ‘toxic debate’, as we have no documented evidence of gender-critical staff or students advocating for or engaging in behaviours such as attempts to de-platform academics with opposing views. An important first step for senior managers in higher education and the organisations that represent them would be to acknowledge the reality of bullying and harassment by internal activists and take on board the lessons of the Phoenix judgment. Staff and students taking part in freedom-restricting harassment should face consequences commensurate with the seriousness of the offence.

The basic recommendation of the Review is for universities and government agencies simply to follow the law. A series of court and tribunal cases provide strong support for the gender-critical position. The Forstater and Phoenix cases confirmed that employees are entitled to protection from discrimination based on gender critical beliefs. The For Women Scotland case confirms that the definition of “woman” in United Kingdom law is based on biological sex. In March, 2025 the Office for Students fined the University of Sussex £585,000 for failing to uphold freedom of speech in the Kathleen Stock case.

The Higher Education Freedom of Speech Act, which will come into force in August 2025, will provide students and teachers in England with new legal remedies when their freedom of speech is violated. The Review recommends that similar protection be provided in other parts of the United Kingdom. Many of the problems identified by the Review could be resolved if universities followed the regulatory guidance of the Office for Students.

The Rest of the World

While the situation in the United Kingdom is hopeful, there are still major problems elsewhere in the world. In the United States, where many of the problems started, the Trump administration has declared war on gender identity theory and the EDI/DEI agenda in general. Major colleges and Democrat-run states are pushing back. Unfortunately, Republicans have not been consistent supporters of science, freedom of speech or women’s rights, so the situation is tangled.

Australia is also changing course. The government of Queensland has suspended the use of hormone treatment for gender dysphoria in patients under 18 and the federal government has ordered a review of treatment guidelines for gender dysphoria in minors. The judge in a recent family court case strongly criticized evidence from Dr. Michelle Telfer, one of Australia’s leading supporters of gender affirming care.

In Canada, the situation remains dire. With the exception of the United Conservative Party in Alberta, no major political party is prepared to challenge the dominance of gender identity theory. Protection of freedom of expression is under attack and most courts and tribunals also appear to support the DEI /EDI agenda.

The most recent controversy has concerned McMaster University, which has a partnership with the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine to produce a series of systematic reviews on gender medicine. Five reviews were registered and the reviews on puberty blockers, hormone therapy and mastectomies have been published.

A group of activists has launched a campaign, using the tactics documented in the Sullivan review, to pressure McMaster to withdraw from the partnership, suppress the unpublished reviews and retract the published ones. The activists have confronted McMaster researchers in the halls and posted videos of the confrontations on Instagram.

The principles of evidence-based medicine were developed by Gordon Guyatt at McMaster. If McMaster can be pressured into withdrawing systematic reviews for political reasons, that would be a defeat for the entire reality-based community.

Thank you! To say that the situtation in Canada is "dire," is, I'm afraid, an understatment. We have serious problems dealing with reality.

Thank you. Your report of the Sullivan Review and the state of affairs in various countries is superb and clearly set forth. I hope it will be widely read and shared.